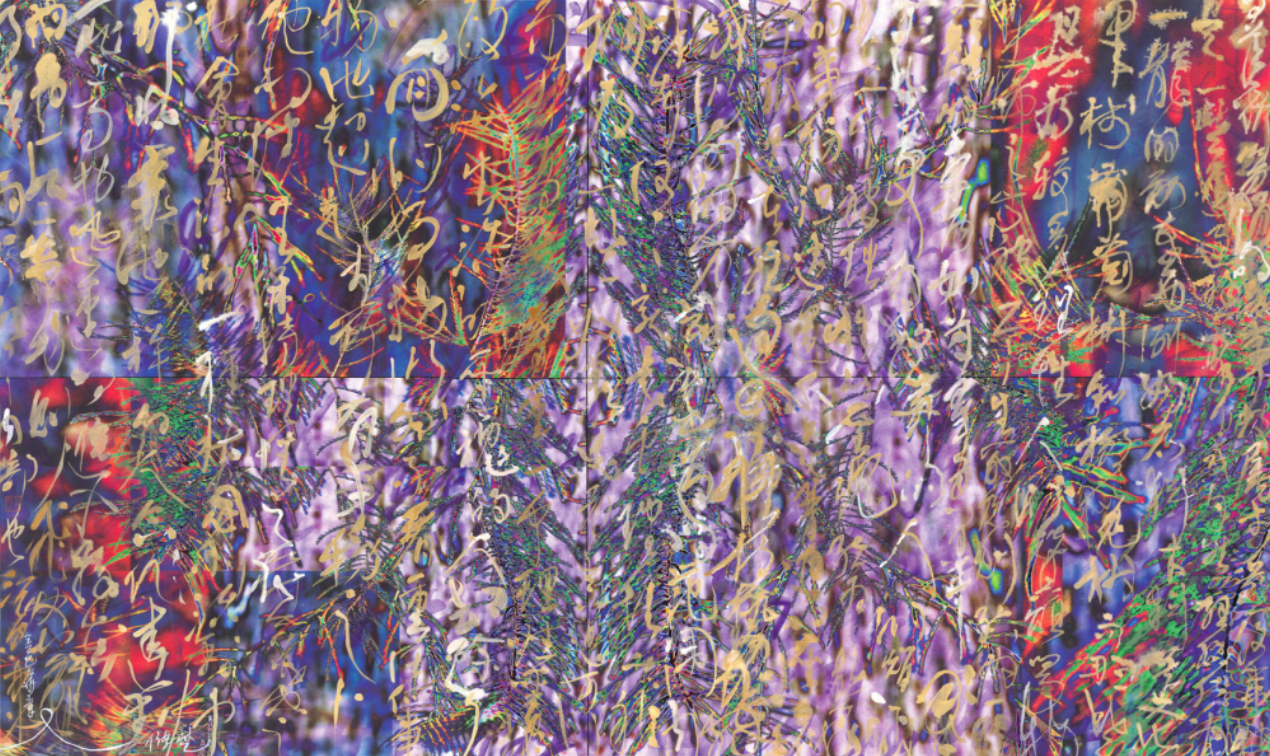

Awakening

WHAT

Having studied at the Department of oil painting at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, the artist has had a very diverse academic background as she also obtained an MFA in new media and a PhD in calligraphy under the tutelage of the famed calligrapher, Wang Donglin. In this second solo exhibition at the gallery, she showcases her works from 2007 until 2022, and the collection of works trace the different stages of her artistic development, highlighting her ever-growing talent. The exhibition features a number of different art forms and overlapping techniques, giving insights into the artist’s daily calligraphic practice.

WHY

The artist’s diverse academic background covering traditional and modern media has led to her unique artistic language. The exhibition presents two main benefits to viewers. The first is the opportunity to see the evolution of an artist over the course of a decade and a half and for those interested to see how Chinese ink painting has developed. The other main enticing factor is the subject matter of the works. From ordinary objects found in nature to the changes in weather from the solar system, the artist discusses a variety of topics that cover the mundanities of life in an extravagant way. In fact, the title ‘Awakening’ aptly originates from the description of ‘Beginning of Spring’, the first of 24 solar terms in ancient China.

**********

AARRTT had the opportunity to catch up with the artist when she was in Hong Kong:

It’s been six years since your first solo exhibition at the gallery in 2017, and now that travel restrictions have been lifted, we have the pleasure of welcoming you back to Hong Kong again, just in time for your second solo. How has your art evolved over the past few years?

It’s important to understand that my artistic practice has (black and white) photography as its foundation and that everything I do is an evolution of my explorations in photography. This is why I used to work a lot in black and white and not in colour, and so my works were definitely more subtle in this respect. Back then, my focus was really on capturing dried fruits, gardenia, and twigs. This formed the building blocks of my work, all of which evolved from photography.

I’ve even done a series of black and white photographs featuring knives – this was in 2009. It was particularly popular with male audiences, who all found portraying blades in such an artistic light fascinating! My female audience didn’t think the same way, though! So to go back to your question, I have gone through different series of works and this depends on my emotions, but photography has remained constant.

What do you do with the objects after you have finished photographing them (in the ‘Material Immaterial’ series)?

I don’t keep the twigs, but I do keep the dried fruits. The twigs have gone back to nature, where they belong. But the memories of their existence linger on through my photographs.

Your newest series of works produced during the pandemic is vibrant and colourful – with calligraphy taking centre stage. How did this come about?

Actually this is a very good question, and one I cannot answer definitively. It’s like how I am unable to predict what my art will be like after tomorrow. Nobody knows!

For sure the pandemic played a role in shaping my art the past few years – whether consciously or subconsciously. It’s undeniable. COVID-19 pushed us into corners, confined us to certain spaces, and imposed restrictions on us (such as tracking our movements via apps). My art is a response to my surroundings and experiences, and my style evolved.

Can you tell us more about what inspires you in your creative process?

My process of creation is closely linked to my lifestyle. In Hangzhou, actually I lead quite an idyllic and even leisurely life, and you can find these parallels in my art. I’m very connected to nature and how the changes in weather affects everything around me. For example, in Jiangnan (area where Hangzhou is located), the weather can get so cold in the winter – minus 7 degrees! And it was also 42 degrees last summer. The heat was unbearable! But despite the extreme weather and difference in temperature between the seasons, I still find the scenery breathtakingly beautiful. Imagine the white snow in the winter, contrasted with the colourful flower blossoms in the summer! My rapport with nature and sensitivity to these changes are reflected In my works.

I also find inspiration in ancient texts and literature. My interest is quite vast, ranging from the ‘Spring and Autumn Annals’ (5th century BC) – one of the five classics of Chinese literature – to William Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet’ (1599-1601). Most of my works allude to literature.

How do you reconcile calligraphy with photography?

When I create, I put in a lot of emotion. The photography part is done quickly, per se; the photo editing is done on the computer using different software. When I’m done with this technology part, I still have to plan what comes next – the calligraphy. This is the part where I have to connect with what’s inside me to trigger an emotion, in order for me to be inspired. Once I am able to connect with the piece in this manner, then I work quickly and efficiently. However, I don’t work continuously until the work is complete. I do pause to reflect, because some works contain several layers and are more complex. At the end of the day, even if the work has been quickly executed, I still spend time to ponder the end result, such as the colour or the effect of ink. There are still many considerations, and I have to be completely satisfied with all aspects.

You have a PhD in Calligraphy, and studied under the tutelage of famed calligrapher, Wong Donglin. Can you share with us what makes calligraphy so special as an art form?

If you’re just looking at my work on a surface level, it looks spontaneous and in some ways even psychedelic, but this is what calligraphy is about! Though it looks easy enough, if you dive deeper you will discover that calligraphy requires not only years of practice, but also meditation and cognizance. You need to develop skill, an eye for aesthetic, and then feelings and emotion. If there is even one element lacking, it doesn’t work.

I learnt calligraphy when I was young, but when I did my PhD, I started developing a deeper understanding of Chinese culture and its rapport with nature. Coupled with age and maturity, different emotions started brewing inside of me, and this helped me grow as a calligrapher. It’s important to possess a certain maturity, an understanding of the world, an experience that has helped you grow.

Abstract works are harder to execute. And if you want to incorporate colour, you really need the right training. You can only succeed in calligraphy if you have to have the right philosophy and the right approach.

What do you hope that your audience will gain from looking at our artworks?

My works are based on photography – black and white. And with my calligraphy, you have to look closely to discover what I’ve hidden in the works. You have to look and you have to explore. It’s a process of searching, and one I hope they will enjoy. It’s like a seed that grows, and slowly develops leaves, then blossoms and bears fruit.

Many artists don’t like to be classified by sex or race, and to be labelled ‘female’ or ‘Chinese’. What are your thoughts about this?

I don’t like to be labelled ‘female’, and it seems that only men would make such a differentiation, don’t you think? But I certainly do not mind being labelled as ‘Chinese’. My development and training as an artist has everything to do with where I was born, where I raised, and where I received my education. There is no doubt that I am a Chinese artist – if you look at my work, you connect those dots right away. It’s the essence of who I am.

**********

Thank you to Chu Chu for the interview.